כשצוללים למים עמוקים: גליה בר אור במאמר על הפעולות בחיפה

גליה בר אור

גרפיטי של בנקסי מצחיק וגם כואב, נראה מתאים לרשימה שמחברת מהפכה עם חיפה ועם משהו מהחוויה שלי בעיר. האבסורד בגרפיטי הזה הוא ביומרת הנצח תוך כדי מחיקה, ומה שמדבר אל הלב הוא הגוף שמצויר בחומריות של שריפה, וניסיון התיקון שמותיר על הקיר את האדום ליפסטיק, כמו כתם דם, אבל ורדרד. בעצם, הציור של בנקסי שבו רואים פועל וכתובת באדום על קיר, נתפס ממבט ראשון כמו קריאה למהפכה, אולי במקסיקו, ויכול להיות שהוא באמת מתאים לחיפה, לא רק משום שחיפה מפורסמת בגרפיטי שלה, אלא, משהו בקיר החשוף ובפועל שאולי הוא אמן, מתחבר לעיר, למשל, הנמל והעיר התחתית. הוא אפילו מזכיר את עברה של חיפה: פועל בשחור-לבן, מסוג אלה שיצר האמן החיפאי הנפלא משה גת, שצמח בשכונת עוני כאן, צייר פועלי תעשייה ופעל בוואדי סאליב. הוא צמח מלמטה, האמין במהפכה חברתית שיש בה מקום חשוב לאמנות, ובמובן העמוק, מדובר באמן שגורל האדם קרוב לליבו.

מהבחינה הזו, אין חזרה לעבר, לא מדובר כבר במהפכה מעמדית, מקסימום אפשר לשמוע שמדברים על מהפכה בתחום טכנולוגי או בשאלה מה תעשה לעולם הקורונה. אבל מראות מעין אלה של בנקסי יש עדין הרבה בחיפה, העיר הזו שריתקה אותי. כי היא עיר של הרבה היסטוריות, חצרות אחוריות, אוכלוסיות שונות ומגוונות, וכל אחת מביאה איתה עולמות שלמים משלה, והיא גם עיר של אמניות ואמנים שפועלים במרחב הציבורי העירוני – כך היתה לפני עשרות רבות בשנים, וכבר אז זה נחשב לייחוד שלה. בשבילי, מבחינת האמנות והעיר, חיפה של היום, היא חיפה של חמודי גנאם, אליזבט קרוגורף, שחר סיון וכמובן רביע סלפיטי ורבות ורבים נוספים שזכיתי להכיר, שהם מאוד שונים זה מזה. אבל, משותף להם, שהם "פרי ספיריט" – חשובה להם החירות הפנימית. הם לא מפסיקים להמציא, כי חשוב להם שבעיר שלהם תהיה אפשרות לחשוב אחרת, לחיות אחרת, ויש להם אומץ כל פעם להקים משהו חדש – כי התנאים בחיפה כידוע לא פשוטים. החשוב הוא שבכל מקום שבו הם נמצאים, העיר מתחילה לחיות. עם אמנים כמוהם, הרגשתי שלב העניין שלי בחיפה הוא ברשת היצירה והמחשבה שהם המוליכים שלה, כמו חשמל, בכוח היוצר שלהם, וזאת רשת גמישה, משתנה, ומייצרת בלי סוף שיתופי פעולה. מבחינה זו ומבחינות רבות נוספות חיפה בשבילי היא העיר שבה אני מרגישה חיה. זו העיר המרתקת בעולם, אני מרגישה חלק ממנה והיא קרובה ללבי.

הגעתי לחיפה מעבודה במוזיאון מושקע שיש לו אוסף שנאסף במשך שנים רבות, הרבה לפני שנולדתי. אמנם המוזיאון הזה, משכן לאמנות עין חרוד, שמר על פשטות וישירות, ובכל זאת, אוצרות וניהול מוזיאון שיש לו אוסף אמנות, נתפס קצת כמו עבודה עם זמן נצח – הנצח של האמנות. כשאת נמשכת למשהו ואת הולכת על זה, את לא מרגישה שאת עושה תפנית יוצאת דופן או מהפכה בחייך, את הולכת אחר ליבך. אולי באיזה מובן גם עשית את זה גם קודם, רק אחרת.

כשהגעתי לפירמידה, גלריית אמנות שממוקמת בוואדי סאליב, עם סטודיואים לאמניות/ים, היה ברור לי בעיקר מה אני ממש לא רוצה: לא להסתגר בגלריה יפה ולאצור בה תערוכות יפות, ולא להתמקד ב"שדרוג אמנים" במסלול הקריירה של עולם האמנות. האמנות המרגשת לתחושתי לא נעשית בשביל האנשים שיש להם הכול, אלא דווקא במקומות הכי חשופים. אם כבר מדברים על פירמידה: אמנות היא לא תפאורה לפרויקט היישוב מחדש של ואדי סאליב. זהו מרחב ציבורי שזוכר את העבר שלו וחושב קדימה עם כל מה שקורה בו וסביבו, והוא פועם אמנות עם האמניות והאמנים שהם חלק ממנו.

לכן שינינו באירועים שלנו את השם, מ"פירמידה" ל- "רציף פירמידה", שממנו יוצאים למסע: לא מתחם סגור אלא צומת לרשת אורבנית שבה המקומות נקשרים זה לזה והכל נמצא בתנועה. אירוע ראשון קיימנו בשיתוף "בתים מבפנים" בין נמל חיפה לואדי סאליב, ועשיתי תוכנית חומש להמשך, לשכונת הדר, קרית אליעזר ועוד. אמנם הפעולה של צאלה קוטלר ושלי נקטעה בפירמידה בשל שינויים פוליטיים, אבל המשכנו לעבוד גם בלי חלל קבוע משלנו. יש איזו אנרגיה של גילוי ויצירה כאשר פועלים במרחב העיר בלא תלות בחלל, בלא בעלות וקביעות – וזאת אולי המהפכה השנייה מבחינתי בחיפה, שהיתה בי גם קודם רק בצורה אחרת. שהרי מההתחלה, עוד בפירמידה, הבנתי שהמקום שלי הוא לחבר רשתות של שיתופי פעולה, שצומחים מלמטה, פועלים בה עם אוכלוסיות מגוונות, וקושרים אותם לאלה שבאקדמיה ובמוסדות המחקר, כמו למשל, הטכניון או האוניברסיטה, ומשלבים אגודות אזרחיות, ארכיונים, וגם את העירייה.

המרחב שייך לכולם. האמצעים הם של כולם, חשובה הנראות והמפגש המשותף באירוע שמתייחס למקום. רשתות חיות שמחברות צמתים הן כוח חיים. אם יגיע שוב מישהו מלמעלה ויחרב את מה שהחל, הוא לא יצליח, כי הוא בא והולך, ואילו הרשת לא משתנה עם חילופי השלטון, היא מתמידה, גמישה, בלתי תלויה.

לכל תקופה המהפכה שלה, אבל שינוי לא מתחולל אם הוא לא צומח גם מלמטה, והיום יש אפשרות לפתח רשתות מורכבות של פעילות אזרחית ושל שיח תרבות, חוצה מגזרים ומיומנויות. אפשר לפתח ביחד מה שמכונה, הון סימבולי, שיוצר משמעויות חדשות וכוח השפעה. למגזין שמארח אותי הפעם, שיוצרים אמנים, אולי אין הון כלכלי אבל יש לו הון סימבולי. הון סימובלי יכול גם להוציא אנשים לכיכרות.

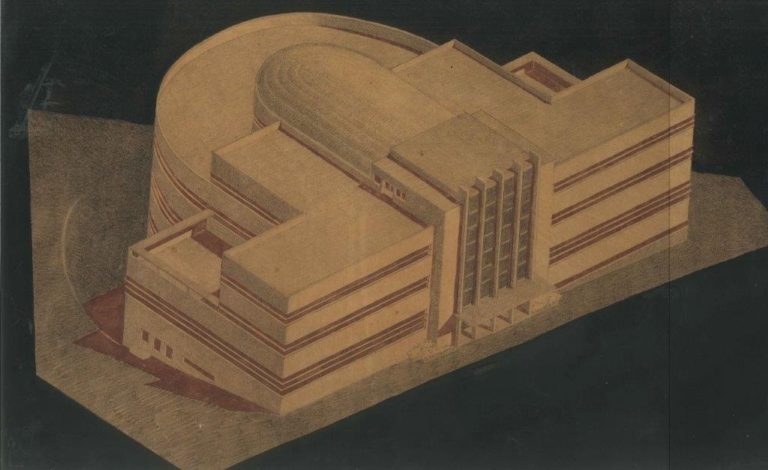

קיימנו את "באוהאוס חברתי, חוויה אורבנית לציון 100 לבאוהאוס חיפה" בהדר הכרמל בסוף נובמבר 2019, ובית הגפן הפיק. השתתפו ב"באוהאוס חברתי" למעלה ממאה אמניות ואמנים שהציגו במספר מתחמים, בחלקם מבנים נטושים, ופעלו ברחובות. מחקר ויצירה, עבר והווה, אמנות ואדריכלות בשיתוף "בתים מבפנים", כנס של הטכניון בהיכל העיריה, תערוכות בבסמ"ת ("הדריון"), קולנוע אורה, בית הפועלים, מקהלת מכוניות באמפי שהפך לחניון, עבודות סאונד, פרפורמנס, מחול, וידאו ארט, ציור, סיורי סאונד ברחובות, תאטרון, וחברו אלינו אנשי השוק, מבקשי מקלט, קבוצות שיתופיות וקהל שהצביע ברגליים.

מבנה שוק תלפיות, גולת הכותרת של אדריכלות חיפה, שרק בשנת 1997 בחנה העירייה אפשרויות להפוך אותו לקניון וכמעט ונמכר, נוקה ביוזמת העירייה והפך ב"בבאוהאוס חברתי" לאתר תצוגה מעורר-לב על כל קומותיו. האמניות והאמנים היו הלב הפועם, משקיעים את הרגישות הגדולה, מהדהדים את ה"להיות לבד" שביחד, מחוללים את הנס, שקושר ופורם ומצית לבבות, נס שעושה עיר. שיהיה באמת מאיפה לקחת אוויר כשצוללים למים עמוקים.

זו היתה דוגמא מה חיפה יכולה להיות, אולי גם זה סוג של מהפכה.

>> לצילומי הצבה מתערוכות באוהאוס חברתי

פורסם במגזין Promise Land Refugees 04.

מאי 2020

Diving into Deep Waters

Galia Bar Or

Banksy’s graffiti is both funny and painful. It seems well suited to this small text, which connects revolution with Haifa as well as something from my own experience with the city. The absurd in this graffiti is its pretense of eternity even as it is being erased, and what speaks to the heart is the object drawn in a materiality of fire and an attempt to repair that leaves red lipstick on the wall — like a bloodstain but of a pinkish hue. In fact, Banksy’s painting of a worker and red graffiti on a wall seems, at first glance, like a call to revolution, perhaps in Mexico. In fact, it may be a good fit for Haifa, not only because Haifa is renowned for its graffiti but also because something about that wall, and that worker — who may also be an artist — that clings to the city, its port, and downtown. It is even reminiscent of the city’s past: a worker in black-and-white, the kind whom the wonderful artist Moshe Gat observed and recreated while growing up in a poor neighborhood in the city. He grew from the very bottom of the city, literally (topographically) and in the economic sense, but was devoted to social revolution, in which art plays an important role. On a deeper level, he was an artist who took the human fate to heart.

In this sense, the past cannot be retrieved. The class warfare has ended. At the most, one can hear rhetoric about a technological revolution or something about the post-coronavirus world. Still, scenes like Banksy’s continue to proliferate in Haifa. This is one of the captivating things about this city. Haifa is a city of many histories, backyards, and heterogeneous and colorful populations, each lending the city its own entire world. It is also a city of artists who operate in the urban public sphere. It has been so for decades and so this remains one of the city’s uniquenesses.

For me, the city and its art, Haifa of today, is the Haifa of Hamody Ghannam, Elizabeth Kroglov, Shahar Sivan, Rabea Salfiti of course, and many others whom I came to know, each very different yet having a strong similarity: their uncompromising “free spirit,” an inner freedom that they treasure. They do not stop inventing because it is important for them to be able to think differently in their city, to live differently, and to have the courage to create something new every time — because the conditions in Haifa, as you know, are not simple. The important thing is that wherever they are, the city begins to come alive. They are like conductors that carry electricity. Yet this creative network remains flexible, and malleable, endlessly inviting collaboration. From this standpoint, Haifa for me, and for many others, is where I feel alive. It's the most fascinating of cities, and I feel like a part of it.

I arrived in Haifa after having worked in a long-established museum with a collection amassed long before I was born. Although this museum, Ein Harod, has maintained its simplicity and directness, curating and managing there felt like a labor of timelessness, the eternal time of art. When you are attracted to something and you just go for it, it doesn't feel like an irregular twist or a revolution in life; rather it feels like following your heart. Maybe in a sense I’ve done this before, only differently.

When I made my way to Pyramida, a contemporary art gallery located in Wadi Salib that exists alongside local artists’ studios, I knew for sure what I did not want: to sequester myself in a pretty gallery, curate lovely exhibitions, and focus on upgrading artists along the regular trajectory of art careers. The exciting art, for me, takes place not in the hands of people who have it all, rather in the most fragile and exposed places. And further about Pyramida: art is not a backdrop, in the sense of a theatre set, for the resettlement of the Wadi Salib neighborhood. Pyramida is a public sphere that remembers its past, thinks ahead with everything happening in and around it, and throbs with art and with the artists that are its own.

Consequently, we renamed the setting of our events from Pyramida to Pyramida Platform, a platform from which you set on a journey — not a closed complex but an intersection to an urban network where places are interconnected and everything is in motion. The first project was a collaboration with the Open House in the area between Haifa Port and Wadi Salib. I also created a plan for the Hadar neighborhood, Kiryat Eliezer, and others.

Although this project of mine, in conjunction with Zella Kotler, was terminated in mid-course due to political changes, we continued to work without a space of our own. An energy of discovery and creation sets in when one operates in a city without being dependent on a place, a landlord, and permanence. For me, this counts as my second revolution in Haifa, something that was previously present in me but manifested differently. All the way from the beginning, starting from Pyramida, I came to the realization that my place is to facilitate collaboration — grassroots collaborations that mesh diverse communities and allies with academia and research institutes such as the Technion and Haifa University, along with civil-society associations, archives, and even the Haifa Municipality.

The urban sphere and its resources belong to all. The visibility and the interaction of the events that create the place are vital. They form a living network that links countless hubs of vital force. Any force that descends from above to destroy the texture is doomed to fail because it is transient. The network, in contrast, does not change when one government falls and another rises; it is perseverant, flexible, dynamic and independent. It is our role to maintain it so that it stays alive.

Every period has its own revolution, yet the changes do not effectively occur unless they flow from the bottom up. Today it is possible to create complex networks of civic activity and cultural discourse that span sectors and skills, and to develop together what is called symbolic capital, the kind that creates new meanings and nodes of influence. A case in point is PLR04, the magazine that’s hosting me. It has important symbolic capital, the kind that can bring masses to the town square.

We planned and created the Cultural Bauhaus project, an urban experience marking the centenary of the Haifa Bauhaus, in the Hadar Hacarmel neighborhood in late November 2019. In the course of the event, produced by Bet Hagefen Arab-Jewish Cultural Center, hundreds of artists participated in exhibitions and performances, some in abandoned buildings and others in the streets. Research and art-making, past and present, art and architecture, collaboration with the Open House project, a Technion conference held at City Hall, exhibitions at Bosmat, Ora Cinema, and Beit Hapoalim, a “chorus of cars” exhibit in an amphitheater transformed into a parking lot, sound installations, performances, dance, video art, painting, and audio tours — all came together with the denizens of the local market, asylum seekers, organized groups, and a crowd that voted with their feet.

The Talpiot market building, the crowning glory of Haifa architecture, which as recently as 1997 was thought by City Hall to be fit for conversion into a mall and was almost sold, was cleaned up by the municipality and became, in the Social Bauhaus project, a thrilling exhibit hall on all its floors. The artists were its beating heart, investing their great passion, echoing the loneliness of togetherness, bringing about that miracle that binds, breaks, and ignites hearts — the miracle that makes a city, that truly provides a place to come up for air when we dive into deep waters.

It was an example of what Haifa could be. That, too, may be a kind of revolution.

Published in Promise Land Refugees 04 magazine

may 2020